Our next stop was the legendary Silk Road city of Samarkand. We arrived as night fell, to find that the number 3 bus that we’d hoped to catch into the city centre was driving around empty and not admitting passengers. We never did quite find out why! Instead, a local chap pointed us towards a tram, so we hopped on and hoped for the best. At least this provided us with another opportunity to play our favourite new game: Public Transit Roulette, where Oli tracks our route on Google Maps and we try by sheer force of will to ensure that we go in the right direction, calling out ‘stick’ or ‘twist’ at each junction, until we have to grab our bags and run to the exit. Unsurprisingly, the house always wins! When we left the train station, we were an hour and 20 on foot from our hotel and we bailed from the tram at 45 minutes from our hotel (not our best result on PTR to date). We began what felt like quite a long trudge in the dark with our bags, but things looked up when we found pizza on the way and we eventually reached the comforting lights of the ‘Ideal Hotel’. What a name.

The next day, we finally made it out and about in the afternoon, after a morning of unrelated faffing while the sun shone (e.g. finding somewhere to do our laundry – an unexpected challenge of Uzbekistan is not being able to do our washing in Airbnbs, since we need to stay in hotels for registration purposes). By this point, the sun had left us and that was the last we saw of it in Samarkand! We decided to start at the Registan, a square bordered by three enormous medressas, since this is the most iconic sight in the city. It was spectacular, even if this doesn’t come through in the photos because the sky was SO grey and threatening.

Tucked away in a small room at the rear of the Tilla-Kari Medressa was an exhibition showing photos of Samarkand and its iconic buildings, streets and bazaars from the past.

This is where we spent most of our time – the photos were so evocative and also helped us make sense of just how much restoration had been necessary.

The Ulugbek Medressa

This was the oldest of the three medressas that make up the Registan (it was completed in 1420) and the first one that we explored.

Inside, there were exhibits showing what had been taught in the medressa, including astronomy, maths and philosophy. Probably the most striking exhibit was the photograph of one of the minarets looking extremely lopsided before it was restored!

The Tilla-Kari (gold-covered) Medressa

Of the three, this medressa looked most different from the black-and-white photographs we had seen in the exhibition. This was largely because of the addition of the turquoise dome, which had been previously unfinished. Our guidebook was rather disparaging about this Soviet addition, but I am a big fan of a turquoise tile so I was on board!

We also read that the ceiling of the mosque in the Tilla-Kari Medressa was actually flat, and that the domed effect was just a trick of perspective. We couldn’t quite believe this and spent ages trying to reconcile this fact with what we could see. (I think it is actually less convincing in these photos than it was when we were there.)

The Sher Dor (lion) Medressa

This was my favourite exterior of the three, partly because of the gorgeous fluted domes but mostly because of the tiled lions on the exterior. Yes, they are stripy and do look like tigers, but apparently that wasn’t the intention!

After the Registan, we moved onto the Bibi-Khanym Mosque, which had a soaring facade and a huge courtyard in the middle. Local legend says that any woman who crawls through the pillars underneath the oversized stone Quran stand (below left) in the courtyard will have many children. It seems that the administration were less keen on this ritual, as it was both fenced off and entirely enclosed in a glass case!

Finally, we visited the city cemetery in the half-light and caught a glimpse of the Shah-i-Zinda Mausoleum complex, to which we would return the following day for a proper visit.

By this time, our luck had well and truly run out and the heavens opened. We all but swam the hour back to our hotel, pausing briefly to admire the Registan by night on our way.

The next morning, it was still raining. Most of my cold/wet weather clothes were still at the laundrette, so I put together a stunning outfit of cropped, wide leg trousers, long red socks and muddy walking boots. If you need style tips, you know where to come.

We first headed to the Gur-e-Amir Mausoleum, which was described in the Lonely Planet as “surprisingly modest”.

I think the author might have been a bit overloaded on Samarkand architecture when they wrote this, because the interior was entirely gold and anything but modest!

The rain got heavier and heavier, so we ducked into an unsigned restaurant behind the bazaar for lunch. At least we hoped it was a restaurant – we just marched straight in! There was no menu, which is my favourite kind of place as the food is always better when they specialise in just one thing. Sure enough, it was the best Plov we’ve eaten so far. As we left (after they kindly tried to persuade us to stay longer to shelter from the rain), I tried to convey by gestures to one of the ladies how much I had enjoyed the food but I think she actually took from this that I was expecting a baby (as she then asked whether we were married – which admittedly would be a slightly strange follow up to me saying I had enjoyed my lunch). We’ll never know for sure, but she seemed absolutely delighted either way!

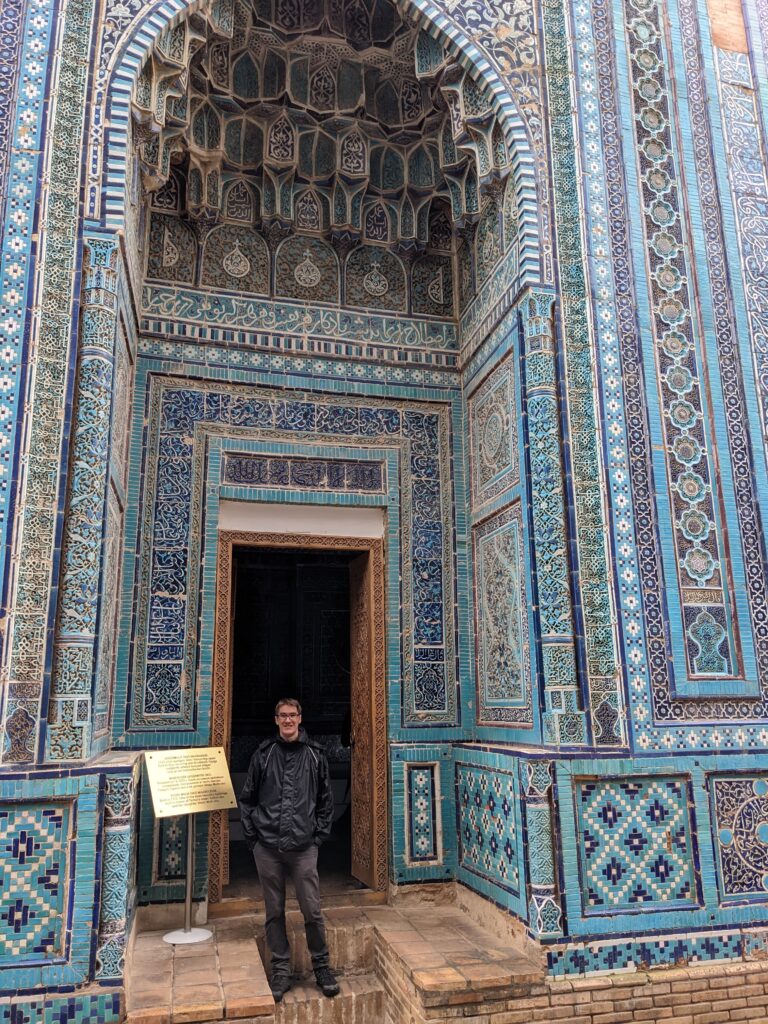

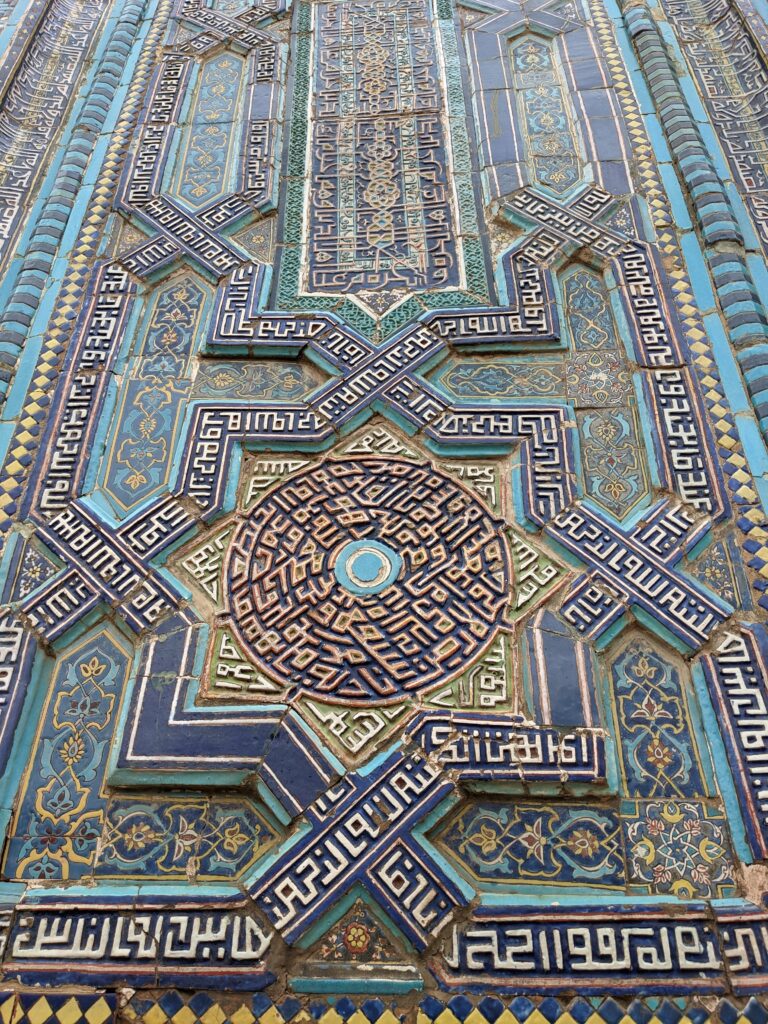

Once the rain eased, it was finally time for a proper visit to the Shah-i-Zinda Mausoleum complex, which consisted of a narrow alleyway with huge tiled mausoleums on both sides. They were truly spectacular, but after extensive (and controversial) renovation work in 2015, most of the tiling is actually less than a decade old, which was rather less impressive. What we did find mind-blowing was that the labelling suggested that they don’t know who is buried in several of the mausoleums. We found it so surprising that these people had been considered important enough to have burial places alongside royalty but their identities were now lost in time.

Our final destination for the day was to take a walk around the old Jewish Quarter of the city, which was tucked behind a large new wall near to the Registan. We’d read that the authorities are very keen to ensure that visitors see only the sides of each city that they deem suitable, and this area didn’t fit the mould. Of course, that only made us more determined to visit, and slipping through the small unmarked gate felt like entering a hidden world.

We spent a while exploring, and came across several local mosques, a synagogue (which served the small remaining community of Bukhara Jews) and even some cats (we’d seen none at all in the rest of Samarkand)!

While we cannot speak for how local people feel about living hidden behind this wall, we struggled to see any tangible benefits of its construction. It seemed a deep shame that investment prioritised hiding anything that might not be fit for tourists’ eyes rather than focusing on local communities’ needs. In any case, we didn’t see anything remotely unpalateable and enjoyed a slice of neighbourhood life – the bakery churning out fresh bread, people out shopping and children cycling home from school. It was a far cry from the sanitised streets around the Registan, home only to souvenir shops and tea houses.

On our way back to the hotel, we stopped for one final view of the Registan, where they were busy building a stage for the finishing line of the Samarkand Marathon, which was taking place just after we left town. Here, we met Ruslan, who comes every day to the area in the hope of finding and chatting to English-speaking tourists to help him prepare for his upcoming IELTS exam. He seemed both excited and flustered to come across native speakers (it sounds like he normally chats to people who speak English as a second language). We had a nice chat about Merlin (the TV show) before getting on our way.

While Samarkand didn’t exactly fulfil our fantasies of a sandy, dusty outpost in the desert (mostly our fault for coming in November), it was very cool to see that it has survived, thrived and is now such a vibrant city. Next, we were very excited to be moving on to Tashkent, Central Asia’s biggest hub and where we had set our sights when we first planned this overland trip on a rainy day during lockdown.