We crossed Thailand twice on our route through Southeast Asia. On the first, we entered Thailand from Cambodia and headed straight for Bangkok’s Chinatown. We then turned north towards the lovely border town of Nong Khai and crossed into Laos.

On our second stint through Thailand, we crossed the Lao-Thai Friendship Bridge at Huay Xai and ate our way through Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai. We then took a sleeper train south back to Bangkok, this time staying in the bustling Sukhumvit area. After a brief diversion to the Death Railway at Kanchanaburi, we continued south through the delightful seaside town of Prachuap Khiri Khan, and finally ended up on the desert island paradise of Ko Adang.

We wouldn’t normally have rushed through northern Thailand so quickly, but we’d read about how poor the air quality can be at this time of year. While we were actually very lucky with our timing and didn’t experience severe haze, the air quality in Chiang Rai has since risen to 125 times the limit deemed safe by the World Health Organisation. We really feel for the people who live there.

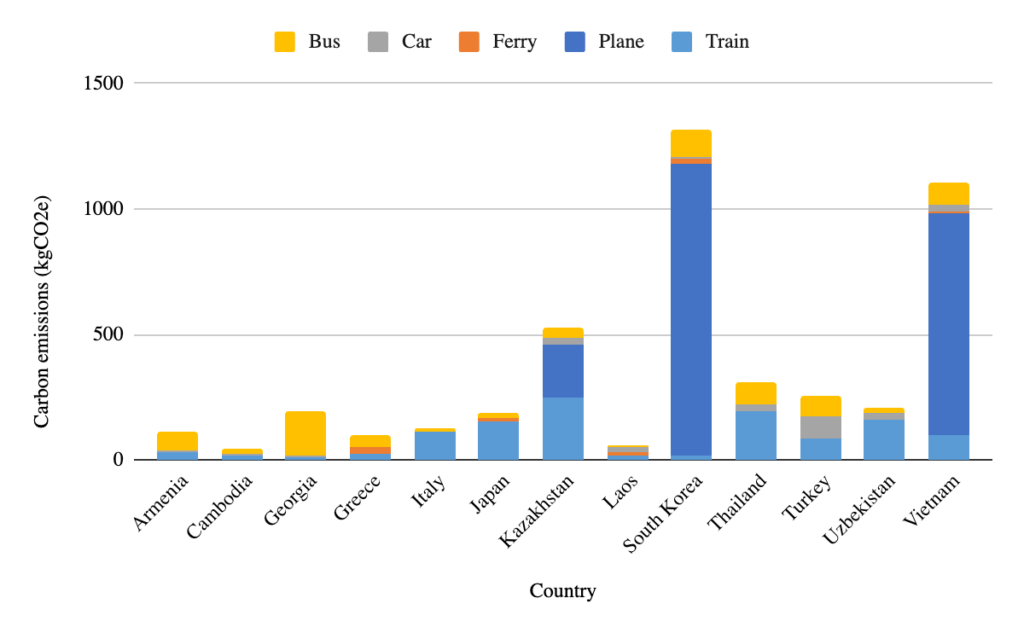

Carbon 🚆

Our travel through Thailand emitted 306 kgCO2e. Excluding flights, this is our second highest carbon emissions within a country to date (after Kazakhstan), although we did cover a grand total of 3,716 km mostly by train during our two transits across Thailand. That’s more than 2.5 times the distance from Land’s End to John o’ Groats!

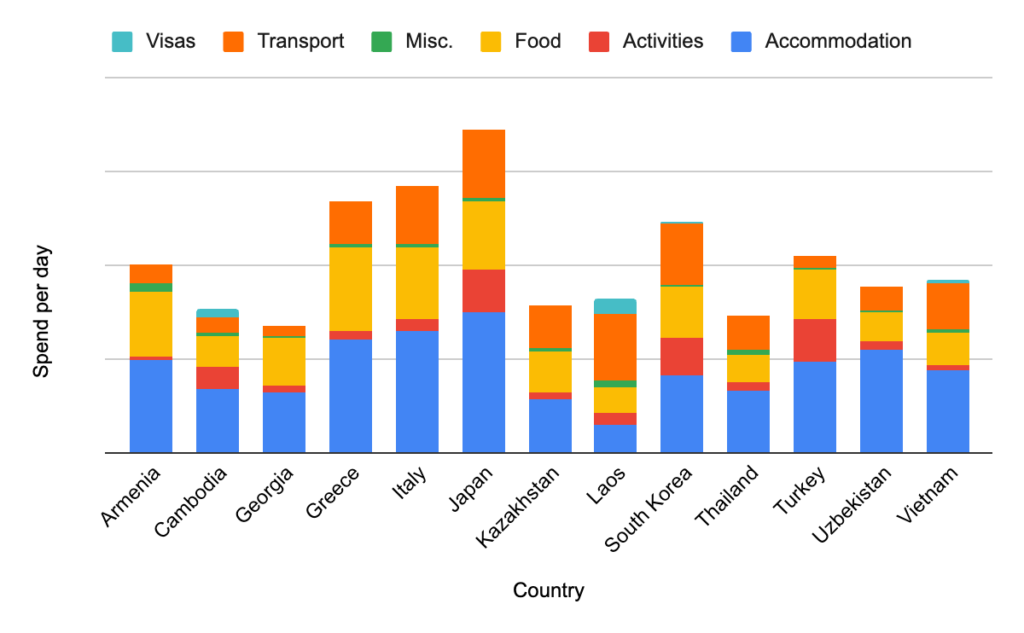

Cost 💰

Thailand turned out to be the second most affordable country we’ve visited, just behind Georgia. To be fair though, we did travel more than three times the distance in Thailand as we did in Georgia over a similar period of time, which explains why our transport expenditure was so much higher in Thailand. In contrast, we saved money on transport but spent it on cheese in Georgia…

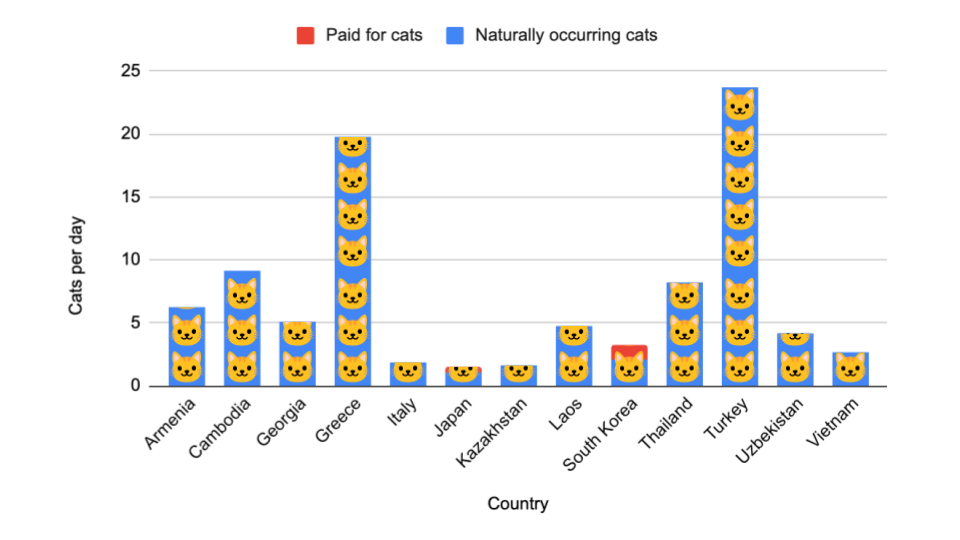

Cats 🐈 (and other wildlife 🐾)

Thailand scored fourth on our cats-per-day metric, just behind Cambodia. We were a little disappointed at Thailand’s final tally of 8.26 as it got off to a very strong start and looked like it might rival Turkey, but the lack of any cats on Ko Adang certainly hurt the grand total.

As well as Thailand’s strong crop of cats, we also came across some other pretty cool wildlife who deserved some serious recognition…

🏅Most fabulous lizard

Lizards are everywhere in Southeast Asia, but this chap’s colouring was on another level. I like to think he was conflicted about whether to blend in or stand out against his surroundings.

🏅Squadron leader, orange corps

We met this lovely chap on the military base in Prachuap Khiri Khan. He was conducting a lunchtime food inspection but was so spoilt for choice that he turned his nose up at the chicken skin Sara offered to him and instead climbed onto one of our neighbours’ laps, where he received a generous helping of prawns!

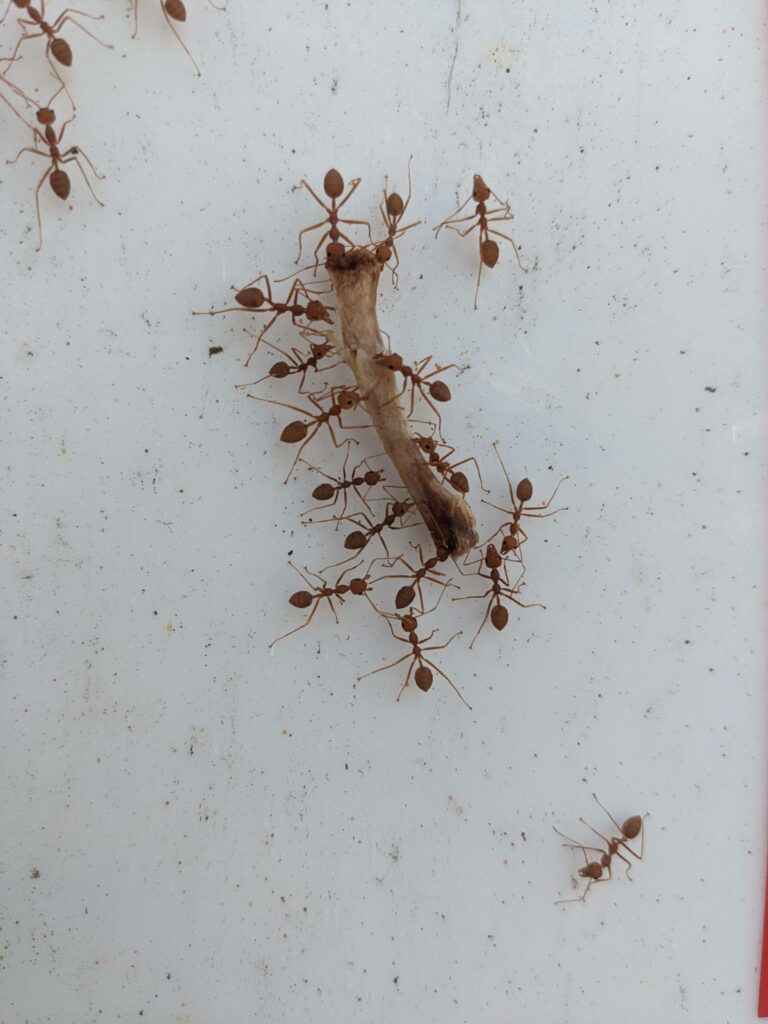

🏅Best coordinated tug of war

Ants are so impressive. Not only are the 12 ants below carrying what appears to be a chicken bone between them, but they’re carrying it straight up a vertical wall! 🤯

🏅Snappiest dresser at the night market

We met the chap below on the promenade in Nong Khai, and unsurprisingly we weren’t the only ones stopping to admire his furry bowtie. He seemed totally at ease with the crowds, and also didn’t seem bothered about being walked on a lead.

🏅Friendliest station master

And last but not least, this chap absolutely stole Sara’s heart. After sharing some of our fellow passengers’ rice, he strolled over and lay down next to us while we waited for our train at Nakhon Pathom. He didn’t even flinch when a huge goods train thundered past honking its horn. I guess this was just another Sunday afternoon for him.

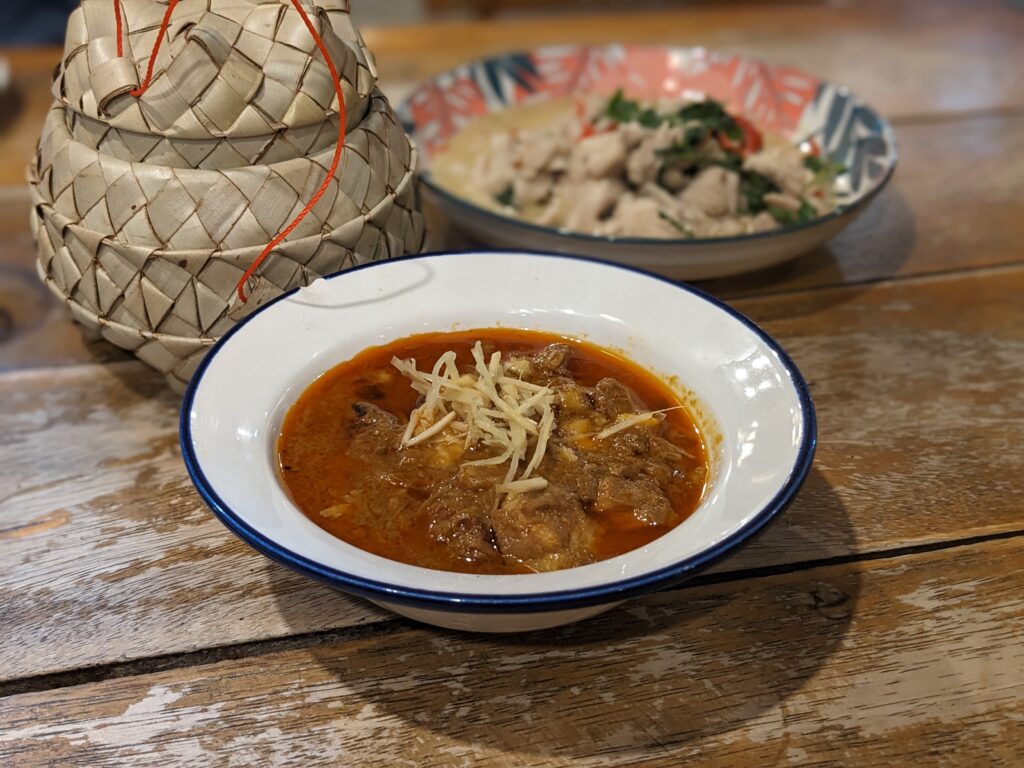

Food 🌶

Thailand certainly didn’t disappoint on its food, although we’ve probably raved enough already about what we ate during our 19 days in the country.

Our one issue is that while it is well known for its spicy food and we also love a chilli or two, we consistently struggled to explain how hot we wanted our food – basically we wanted to eat the original version of the dish, without any chilli added or taken away. Many restaurants suggested we take the food “medium spicy”, which on the face of it sounds like a good call, but we couldn’t shake the feeling that some dishes had been watered down to suit Farang tastes and often ended up too mild for our liking. We also tried “as you would have it”, though I think that was just too subjective. Our struggles reminded me of a spice scale we once saw in a restaurant that had Athens at the mild end, London in the middle, and Delhi at the spicy end. This is what we needed!

The UK FCDO currently advises against all but essential travel through much of the area north of the Thailand-Malaysia land border. This left us in a bit of a predicament, as it ruled out both rail crossings and most road crossings between the two counties. That was until Sara came across a ferry connection between the Thai island of Ko Lipe and the Malaysian island of Langkawi, both of which we were excited to visit. Phew!