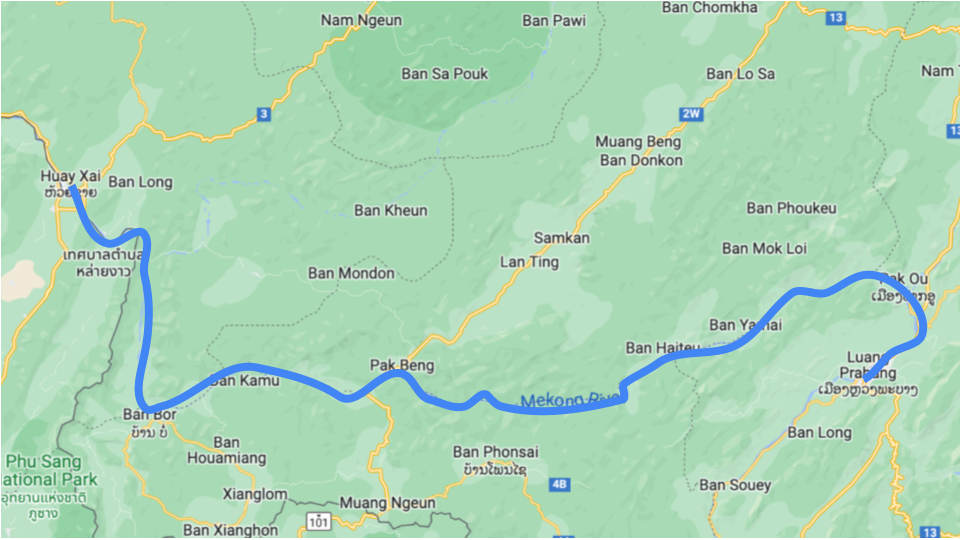

We’ve met up with the mighty Mekong River quite a few times over the last few weeks – first in the huge Mekong Delta region of Southern Vietnam, then again in Phnom Penh (Cambodia), Nong Khai (Thailand), Vientiane (Laos), and finally in Luang Prabang. Now, it was time to get properly acquainted as we were to spend two days sailing upriver on the ‘slow boat’ to Thailand.

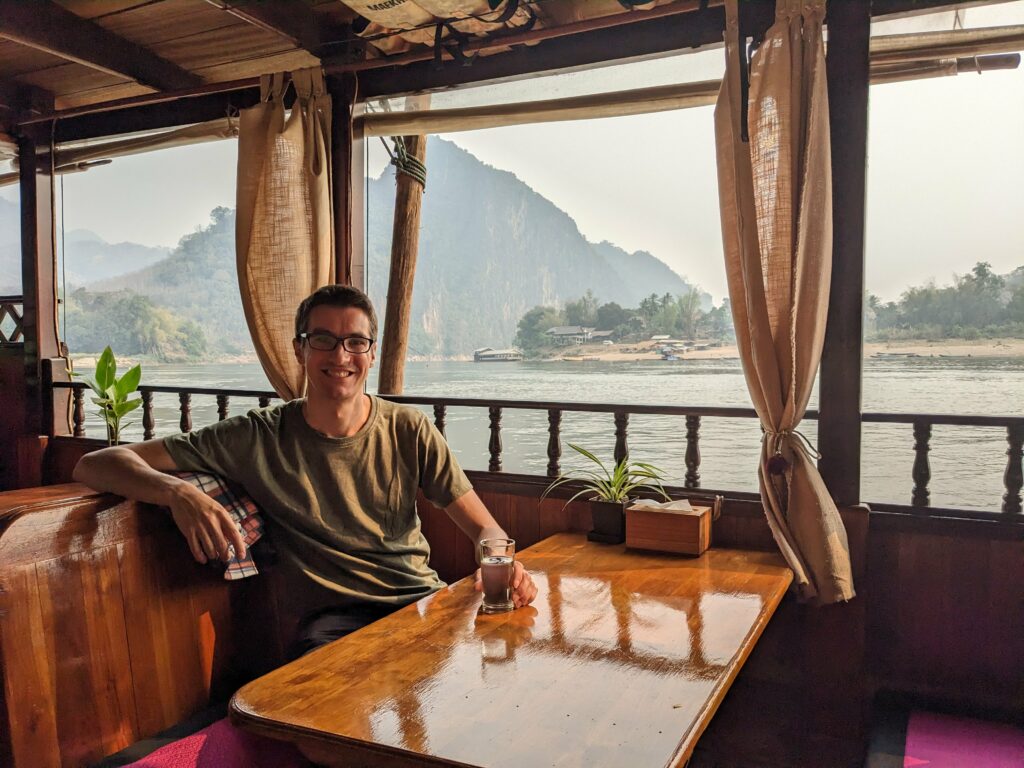

I should probably confess that our journey wasn’t to be on the original slow boat, the public ferry that makes its way up and down river daily, stopping at local settlements on the way. We’d read that this can be a great experience but quite cramped, which is fine for a few hours but maybe less so for 10 or more hours a day. We decided that if we were going to spend two days on the water, where the journey was the destination, we should make the most of it. All this to say that we talked ourselves into a private slow boat, complete with lovely lunches, day beds (my favourite!) and a couple of interesting stops en route. We already felt a bit guilty about our uncharacteristically extravagent decision but even more so when we boarded and found that we were two of only five guests on board (the boat had capacity for 30) – not particularly good for our carbon credentials!

We set sail from lovely Luang Prabang just before dawn, and before long the sun peeked over the hills next to the riverbank.

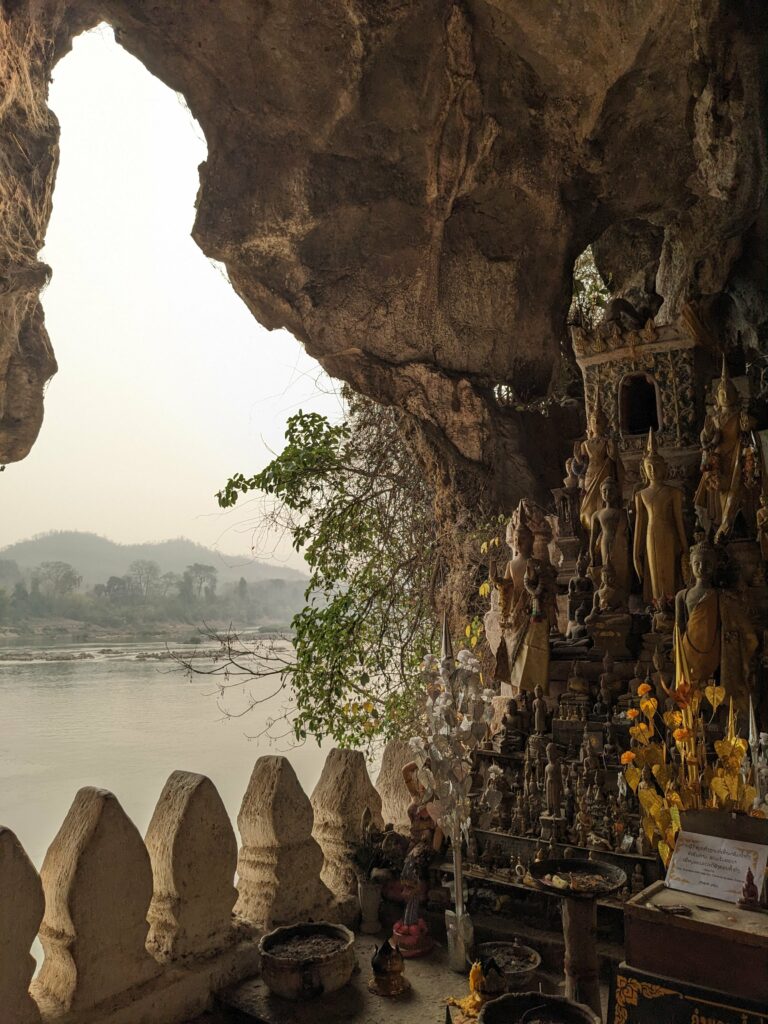

We spent the next few hours gazing out of the window at the landscape and eating our second breakfast (in true Vicar of Dibley style, we didn’t like to tell the lovely family who were looking after us that we’d already eaten), before making a brief stop at the Pak Ou Caves. These caves are full of Buddha images small and large, and are a favourite annual pilgrimage site for Laotians, who bring their Buddha images from home to pray with them.

In exchange for a donation, I picked up a Lao version of the omijuki we’d selected in Sapporo to tell us our fortunes at New Year, and once we were back on the boat, I asked our guide to help us translate it (Google Translate having been even less help than in Japan). He said that a lot of it was quite abstract so I imagine he had to exercise some artistic licence in interpreting it, but that, “If you have a sales business, it is good for your future,” [well I don’t, but noted] and that, “Your love will love you much more in the future” [so maybe the tide will turn and Thomas 🐈 will prefer me to Oli one day!]. It all sounded very promising, although I do wonder what he wasn’t telling me, as there was a bit more written than that…

Because of the meanders in the Mekong’s route through Laos, we passed twice under bridges that carry the Lao-China Railway up towards China. As far as we know, there aren’t any trains running along this route at the moment (we’ll have to come back one day) but it was still incredible to see the sheer amount of concrete supporting this huge infrastructure project.

It looked so out of place on the banks of the Mekong, where we had drifted past little more than small settlements, herds of buffalo and cows, bamboo fishing rods, and local people out panning for gold. In fact, the very largest settlement we saw was the town of Pak Beng, where we arrived around sunset of our first day to spend the night. This was the biggest town for some distance, but that’s not saying much – below is the quiet main street.

After a night spent in our simple (but perfectly adequate) £10 guesthouse (our attempt to balance the books after splashing out on the private boat!) we headed back down to the jetty for another pre-dawn start. Soon after, we made a stop at a riverside village for a quick wander.

We weren’t quite sure how we felt about this, to be honest. Although I love to see how other people live (one of the great joys of travel), I do think there’s a fine line between this and flat-out voyeurism. And this was no slick, rehearsed, inauthentic tour-group stop, but a tiny, remote and obviously quite deprived village. We understood from our guide that there is a financial agreement with the Village Chief so that the local people benefitted from our visit and that the village is changed regularly so that these benefits are distributed in the region, but I’m still not totally convinced that our presence was really welcome or helpful. So, whilst another member of our small group was photographing the children (which didn’t feel quite right), we focused on making friends with the piglets who were roaming around freely.

After an absolutely spectacular buffet lunch (the family on whose boat we were travelling looked after us SO well), the remainder of our second day was spent much as the first. We gazed out of the window at life on the banks of the Mekong, napped on daybeds, listened to podcasts (my current picks are Table Manners, Desert Island Discs and More or Less, in case you’re wondering – please send more recommendations my way!), caught up on this blog, and made some onward travel plans. It was an incredibly peaceful way to travel.

Around 4pm, we passed under the Thai-Lao Friendship Bridge IV, which marks the western border crossing between the two countries, and docked on the Lao side of the river in the small town of Huay Xai. Here, we watched the sun set over the Mekong one last time, before crossing the border to begin our journey south through Thailand the following day.