We were genuinely quite sad to move on from Nong Khai – it was such a lovely town and we’d just had the most restful few days of our entire trip. Our guesthouse host Julian (a chap from the Cotswolds, of all places) kindly gave us a lift to the border, and despite reading many stories of all the spurious ‘fees’ we would need to pay to the border guards, we sailed through in no time and with no nonsense. We couldn’t believe our luck when a green local bus was waiting as we came out, as we’d read that it could be difficult to find. When a taxi driver threw himself in our path to tell us that it was going to the wrong place (not that he knew where we were heading) and that we would have to walk a “long, long way” unless we got into his taxi, this only gave us more confidence that this was indeed the correct bus, otherwise he wouldn’t have been so concerned with stopping us getting close enough to check the number. “Great,” we replied, “We like walking!” He did not look impressed.

We’d read that Vientiane was Southeast Asia’s most relaxed capital city, and it really was – in fact, I reckon it would probably be in the running to win a worldwide contest. We borrowed bikes from our hotel (which were free – we were soon to discover why when we actually tried to ride them) and set our sights on Vientiane’s biggest sight and national symbol: Pha That Luang.

The legend is that a stupa was built here as early as the 3rd century BC to enshrine a piece of Buddha’s breastbone. Through a series of paintings depicting the stupa, we learnt about its history, from first construction, to repeated plunder by various occupying forces, to restoration by the French in 1900 and finally painting it gold to give it today’s appearance. Only the very tip of the stupa is real gold, and we think we could see it glinting a little brighter in the sunlight.

Although this was the city’s biggest sight, it was blissfully quiet, further cementing Vientiane’s reputation for us. The temple next door was a totally different story – there seemed to be a party in full swing! We had to walk through this to get back to our bikes because, in usual style, we’d inadvertently approached Pha That Luang through a side entrance. But we were glad we did, as there was a really joyful atmosphere, with food stalls, an open-sided marquee where people were eating together, and at least two sets of competing music. The following day was a religious holiday so we assumed that the two were related, but who knows – perhaps every Sunday is like this.

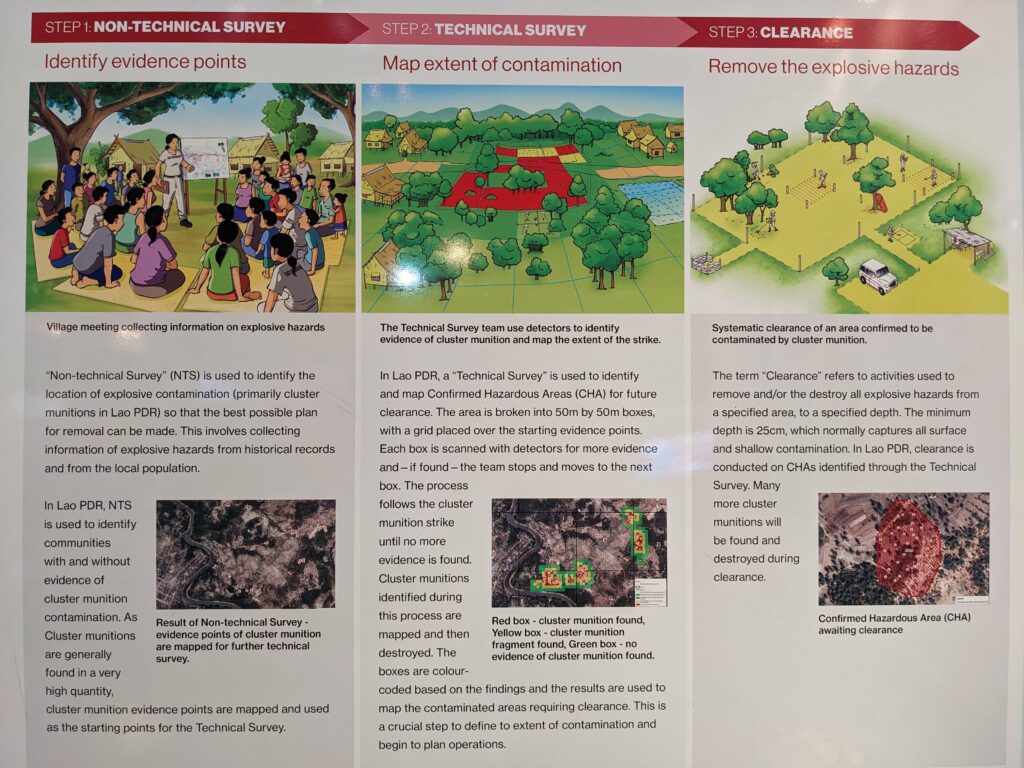

Later, we cycled to the COPE (Cooperative Orthotic & Prosthetic Enterprise) Visitor Centre, which had been highly recommended. Even to this day, Laos is the most heavily bombed country in the world (per capita), following the bombardment they suffered during the Vietnam War, and unexploded ordinance (UXO) in the form of cluster munitions still contaminates 25% of villages across the country. Because of this, everyday activities such as farming and cooking are hugely risky and a source of great anxiety for Lao people living in uncleared areas. We learnt about changes that had been made in the data-driven process used to plan and prioritise clearance activities and the impact this had had on the speed at which areas are cleared, which was such a brilliant illustration of the power of data (not that we needed much convincing).

One of the most surprising things we learnt was that some resourceful people use the metal from the casings of ‘bombies’ (as they are known locally) in all sorts of everyday objects around the house. Because of the familiarity that this breeds (and the lure of the scrap metal trade, which is technically illegal but still widespread), children in particular are at risk of forgetting what they have been taught about UXO when they find a metal object. Tragically, this means that 40% of those killed or injured by UXO are children. The centre described the ongoing outreach work that aims to change this, by removing (with permission) these everyday objects made from ‘bombies’ from communities and reinforcing teaching in children about the risks associated with UXO. Finally, we learnt about the work that COPE is doing to provide affected people with prosthetics and ongoing support.

To be honest, we didn’t really expect to end up in the visitor centre of a rehabilitation charity during our brief time in the city, but then again, we didn’t find a whole lot to do in Vientiane. This does a massive disservice to the centre though, because it turned out to be a very worthwhile stop – the exhibits were in equal parts fascinating, devastating and inspiring and gave us a real insight into Laos’ story.

Our final stop in Vientiane was the city’s very own Arc de Triomphe replica, Patuxay. This was built in the 1960s using concrete donated by the United States but intended for use in construction of a new airport, which made us chuckle. Although the exterior looked like a little slice of Paris (and was surrounded by a roundabout just like the original), our favourite part was the tiling on the interior of the soaring arch, which was inspired by the Taj Mahal.

Next, we were very excited to have secured (through a slightly bonkers system) tickets on the Lao-China Railway to take us on an inconceivably-speedy, 2-hour ride to Luang Prabang, a journey that can take literally days by road.