As we mentioned in our last post, Nukus didn’t exactly come highly recommended by the Lonely Planet. But we needed somewhere to break our journey through western Uzbekistan and to be honest, we were a little curious about how bad it could really be! We also read that it has a world-renowned collection of proscribed Soviet art on display at the Savitsky Museum.

Although you’ve probably gathered by now that neither art nor museums are our usual style, it seemed silly to miss the main thing that brings most visitors to the city (although still not a great deal of visitors – after all, it is 22 hours by train from the capital, Tashkent). In another departure from our usual style, we decided to hire a guide, since we are totally clueless about art and anticipated that otherwise we might just wander around blindly, occasionally uttering a perplexed, “Huh”. Ahmad did a great job of bringing the museum to life (and told us some good stories of his own, including the time that he sent Elon Musk a private message to say that he would help him launch Starlink!)

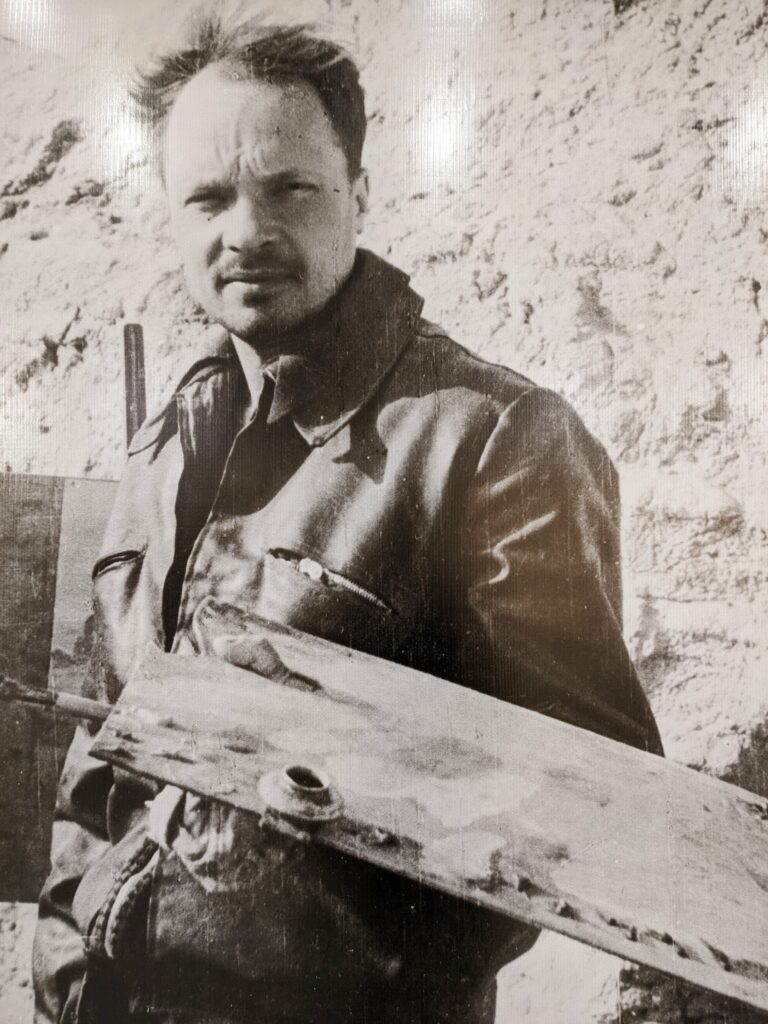

Igor Savitsky was a man on a mission. A painter himself, he had travelled to Karakalpakstan in the 1950s as part of an archeological and ethnographic expedition and came across many avant-garde artworks hidden away because they didn’t conform to the socialist realism style that was all but required by the state in the 1930s. Determined to save them, he dedicated (and risked) his life to amassing a huge collection of more than 82,000 pieces and giving them a safe home. Apparently, only 5% of these are on display at any one time, and that’s when both buildings are open (one was closed for renovation when we visited – a bit of an ongoing theme in Uzbekistan).

The collection doesn’t just include paintings, but all sorts of other Karakalpak artefacts from textiles, jewellery and ceramics to Zoroastrian ossuaries (below right). I had a bit of a shock when Ahmad explained to us that the red outfit (below left) would have been worn by young women, and the white outfit by elderly women aged over 40. When I tried to clarify if this really meant that I would become an elderly woman the day after my 40th birthday, he unapologetically agreed that yes, this would indeed be the case!

Despite this shock, we really enjoyed Ahmad’s humorous and accessible style – he described the painting below of animals at a water trough as an ancient gas station.

The painting below apparently depicts the different stages of drinking – in case you didn’t guess, it was around about now that Ahmad produced his story about Elon Musk…

I loved this painting – it is a family portrait by Serekeev Bazarbay. The baby in the centre is the daughter of the painter and now works at the museum – how cool to have a family portrait on display where you work! Apparently she sometimes does tours and people never believe her when she says, “That’s me!”

Ahmad told us at the start of his tour that he would point out his favourites when we got to them (having been brutally honest about some others of which he wasn’t a fan!) and brought us to this collection of paintings of the Aral Sea. Due to a combination of poor land management (for instance, diverting water to grow cotton in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, countries that have poorly suited climates) and climate change, the Aral Sea has all but dried up. For a combination of reasons (time, distance, not wanting to gawp at others’ misfortune), we’d decided not to visit Moynaq, but we’d seen plenty of pictures of ships beached in arid desert (in fact, I think it’s shown on Race Across the World). It has been described as one of the biggest environmental disasters of all time, and seeing these paintings of such a thriving fishing town really brought home what a catastrophe this was. Apparently these two painters, who had devoted their lives to painting the Aral Sea, stayed in town after it had retreated and each poured a container of water on the dry sea bed every day as a symbol of their hopes that it would return.

On a happier note, these were some of my favourite paintings and really got me excited for the Silk Road cities that lay ahead.

Overall, Nukus was a pleasant enough city and not at all deserving of Lonely Planet’s searingly disparaging description – I wonder whether the authors have visited many grim British towns as they could definitely give it a run for its money! We did read that there had been some sprucing up in recent years to help shake off Nukus’ reputation, so this might explain it.

It was time for us to head east towards our next stop in Uzbekistan. We did this via one of the most chaotic transport interchanges I have ever experienced (and I see myself as a bit of a connoisseur!), the marshrutka station at Nukus’ main bazaar. This is a view of it from above, but it does little to convey the sheer chaos that was unfolding below.

There’s something really humorous about seeing these tiny minivans zipping about everywhere – they are driven so aggressively, almost as if to counter their cute appearance. Oli is a big fan!

By some small miracle, we managed to cram ourselves onto the correct marshrutka and were on our way to the Silk Road city of Khiva.