We arrived in western Kazakhstan by plane from Yerevan, and continued overland by train into Uzbekistan. Our original plan had been to cross the Caspian Sea by ship, but since Azerbaijan’s land borders were still closed, flying from Armenia was our best option.

Emerging from the eastern end of Uzbekistan, we travelled from Shymkent to Almaty via Astana. While it would have been shorter to travel via Almaty and end this leg in Astana (rather than vice versa), this would have drastically reduced our onward flight options, and crucially ruled out direct flights to South Korea.

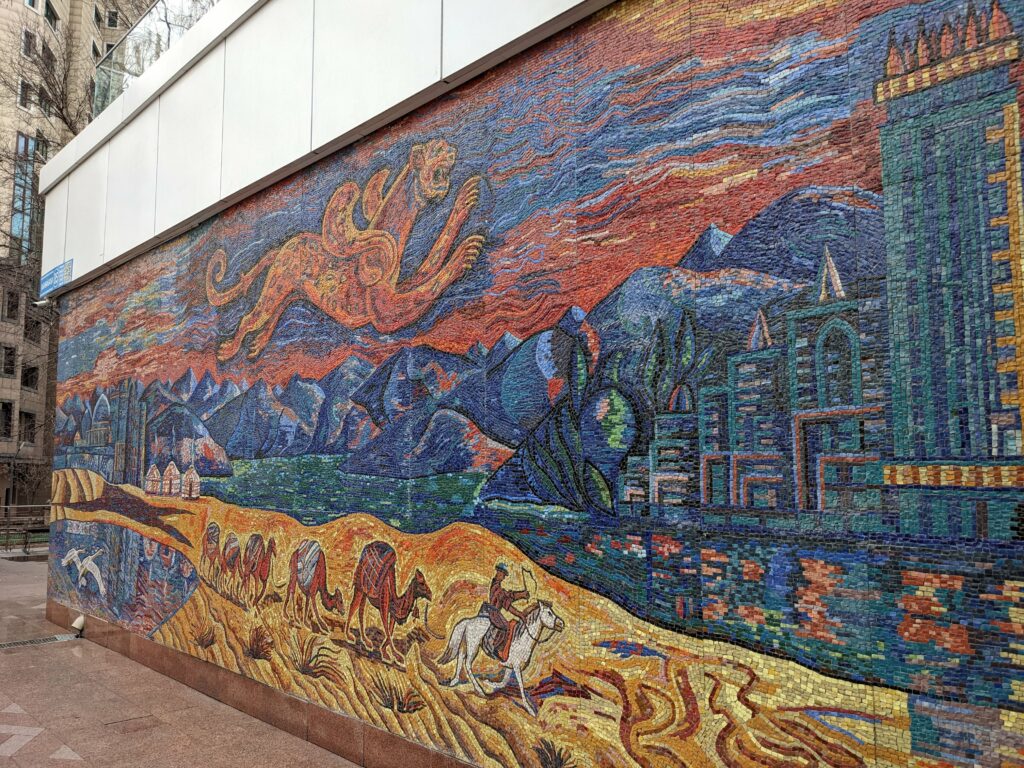

Throughout Kazakhstan we were amazed at how modern everything was. I’m not sure whether our shock was just due to naivety or the stark contrast with Uzbekistan, but it certainly made getting around relatively stress-free.

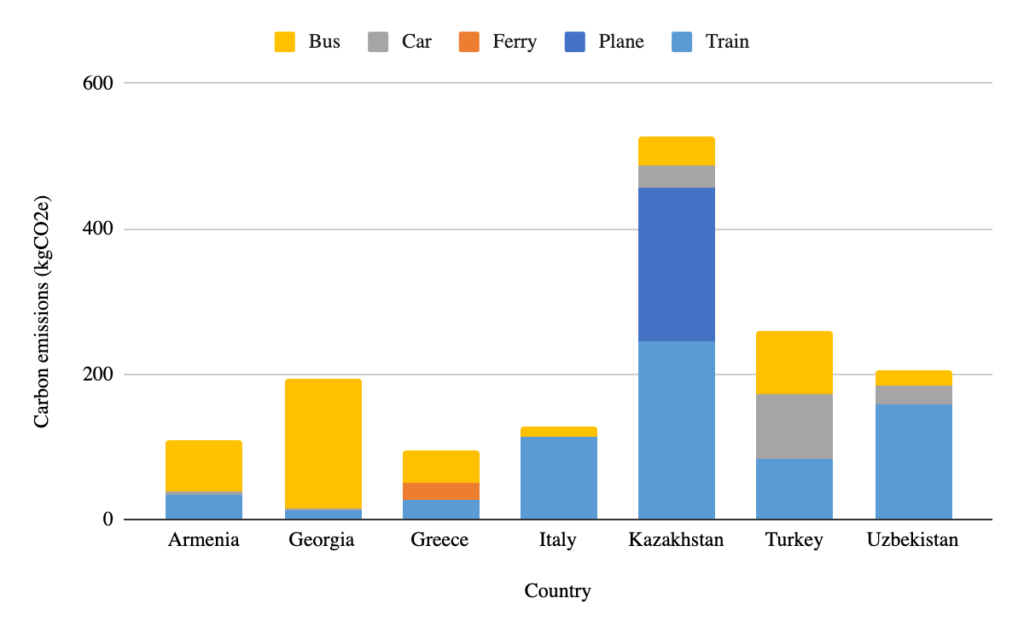

Carbon

Our 1 hour flight across the Caspian Sea emitted nearly as much carbon as our train travel throughout Kazakhstan, despite us travelling nearly 5 times further by train than we did by air. We also enjoyed travelling by train a lot more, given that a night spent on a sleeper train was a whole lot more comfortable than a night spent on a flight.

We travelled 4,400 km across the Caspian Sea and through Kazakhstan – our longest distance travelled in any single country so far. This goes some way to explaining why Kazakhstan also tops the carbon leaderboard by a significant margin.

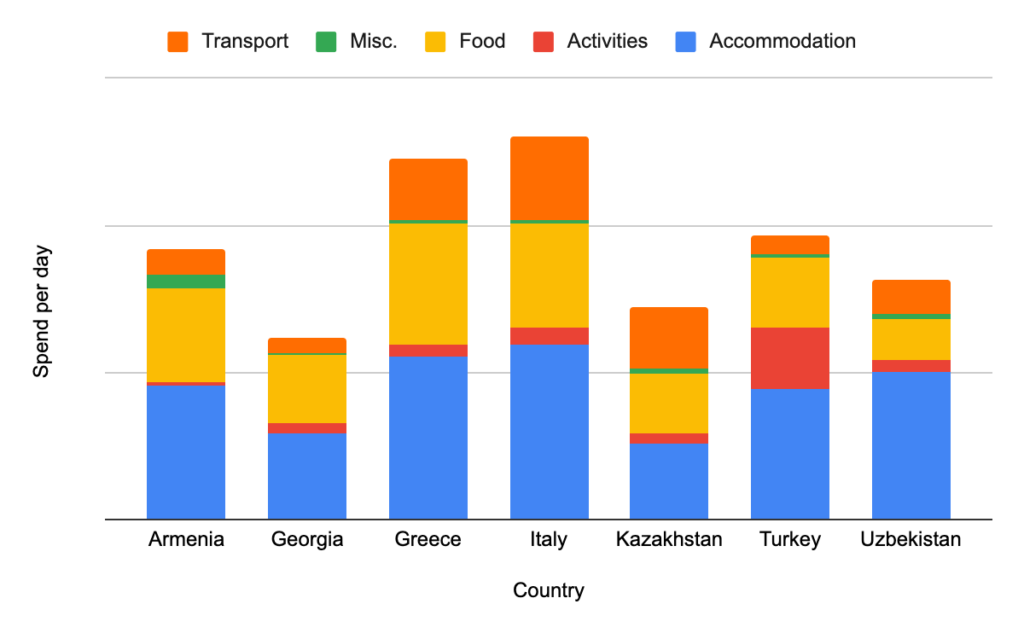

Cost

Kazakhstan was pretty affordable, with us spending almost as little per day as in Georgia. It’s also unsurprising that a large proportion of our expenditure was on transport given that we took our first flight of the trip to get there, as well as travelling the longest distance overall.

In general, we found Kazakhstan to be a very tourist-friendly country. However, our one annoyance was Kaspi – the Kazakh electronic payment system which was pervasive throughout the country, yet completely inaccessible to foreigners. This was brought most painfully to light on a bus journey back from visiting the ALZhIR museum just outside of Astana. Despite paying by cash to the driver on the way, a conductor boarded the bus on our way back who wouldn’t accept our cash, and instead pointed us towards the Kaspi QR code on the wall that everyone else had used to pay. In the end, a couple of kind fellow passengers paid our fares by Kaspi, but then wouldn’t accept our cash in return, and instead wished us all the best and to “stay safe and enjoy Kazakhstan”. This moment was both excruciatingly embarrassing and totally heartwarming in equal parts.

Cats

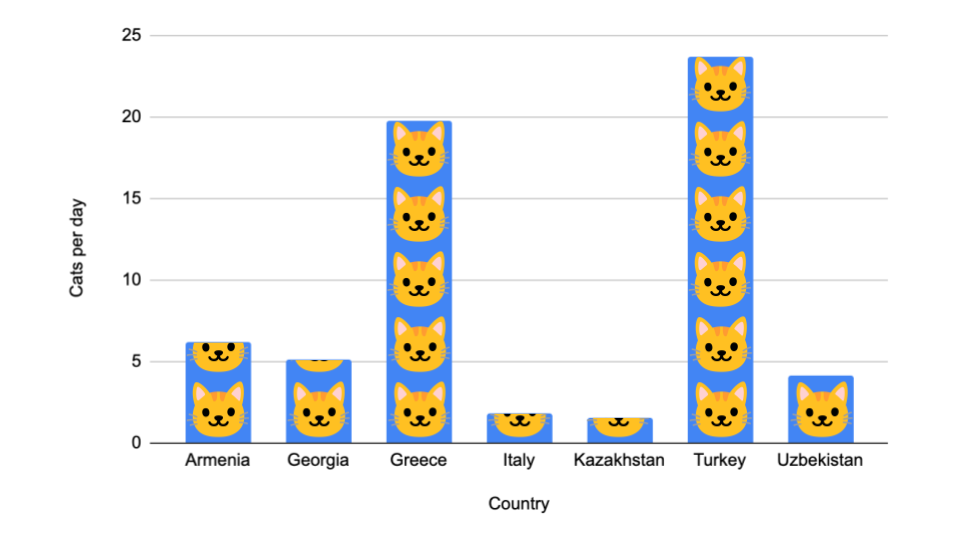

Sadly, Kazakhstan has taken Italy’s spot with the lowest cat density of any country we’ve visited since leaving London, with only 1.6 cats per day. To be fair, it was incredibly cold when we visited some Kazakh cities, so who can blame the cats for sheltering inside?

Still, we did see some exemplary cats (and an honourable mention) during our two-stage visit to Kazakhstan.

🏅 Floofiest floofer award

At least this chap knew how to dress for the Kazakh winter!

🏅 Best aerial display

While the cat on the left was a little unexpected, we almost missed the owl chilling in a tree outside one of the crypts near Aktau – he was so well camouflaged! Although he didn’t make a sound, his one open eye did watch us everywhere we went.

🏅 best behaved kittens

These cuties were told to “stay put” in the dry while their Mum went off to hunter-gather some dinner outside a restaurant in Aktau. At first we thought they were alone, until we heard their mother padding about on the roof above our heads!

Food

We ate really well in Kazakhstan, although admittedly this was mostly international food. We’ve already talked about our experience with Kurut (Kazakhstan’s national snack), but our train friends also recommended that we try Beshbarmak (the national dish). This comprised of horse meat and sausage in broth, on a bed of wide, flat noodles with a lone boiled potato as the centrepiece. I thoroughly enjoyed it!

Beyond Kazakhstan, our first choice would have been to continue overland through China, but it’s still not possible to get a tourist visa at the moment. Our backup plan was to fly to Southern Asia, but India’s e-visa system was still suspended for British citizens and we weren’t keen to surrender our passports for a full visa. Instead, we settled for a slightly longer flight to South Korea, the home of K-pop and kimchi 🇰🇷