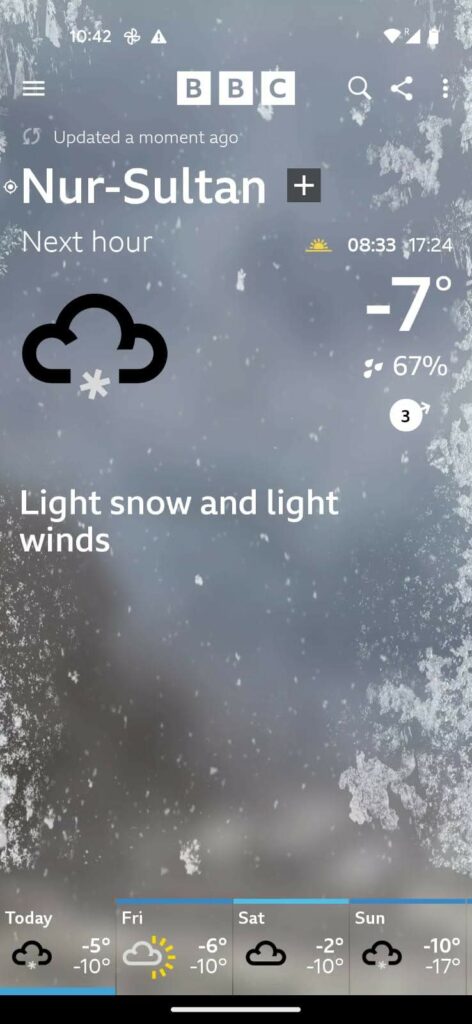

Astana is the capital city of Kazakhstan and at 51 degrees north, is a long, long way up from where we’d been travelling east (at around 37-45 degrees) since we left London.

This probably should have served as a bit of a clue that the November weather might be rather chilly, but somehow this didn’t factor into our conversation at all when I was trying to persuade Oli that it was a great idea to go!

Actually, it turned out that the snowy weather really made our visit, and our careful packing for four seasons just about kept us warm enough. It did make walking everywhere a bit of a challenge – we still tried but the buses were pretty enticing at times!

It turns out that Astana holds the Guinness World Record for the capital city with the most name changes, having first been called Akmolinsk, then Tselinograd, then Akmola, then Astana and finally Nur-Sultan. In fact, the city has had another name change even since we left home in August – we’d been there a few days before we realised that it had in fact reverted to being called Astana from Nur-Sultan (we just assumed everyone referred to it by its old name still). It’s hard to keep up!

Our first activity when we stepped off our overnight train was to visit the iconic Khan Shatyr shopping centre. This might sound like an odd place to start, but it was warm inside and apparently of architectural merit (having been designed by the British architect Norman Foster).

Of more interest to us was that it had a monorail running around the interior, which we just had to ride.

One of Astana’s most iconic buildings (and the one I’d seen in photos that really made me want to visit) is the Bayterek Monument, which sits right in the centre of the city. We took a lift to the top, which had great views of the snowy surrounds and gridlocked traffic, and saw former President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s golden handprint. The idea is that you place your hand in the print while looking towards the palace (if this seems a little egotistical, that probably does a good job of summing up how presidents are treated here – after all, the whole city of Astana was named after him for three years).

We saw more cool architecture surrounding Independence Square – the city really has gone big on futuristic buildings.

Although we’d normally love to take our time walking around an area like this, it was bloody cold! Oli resorted to Labrador techniques to keep warm (and my fingers nearly fell off taking this video).

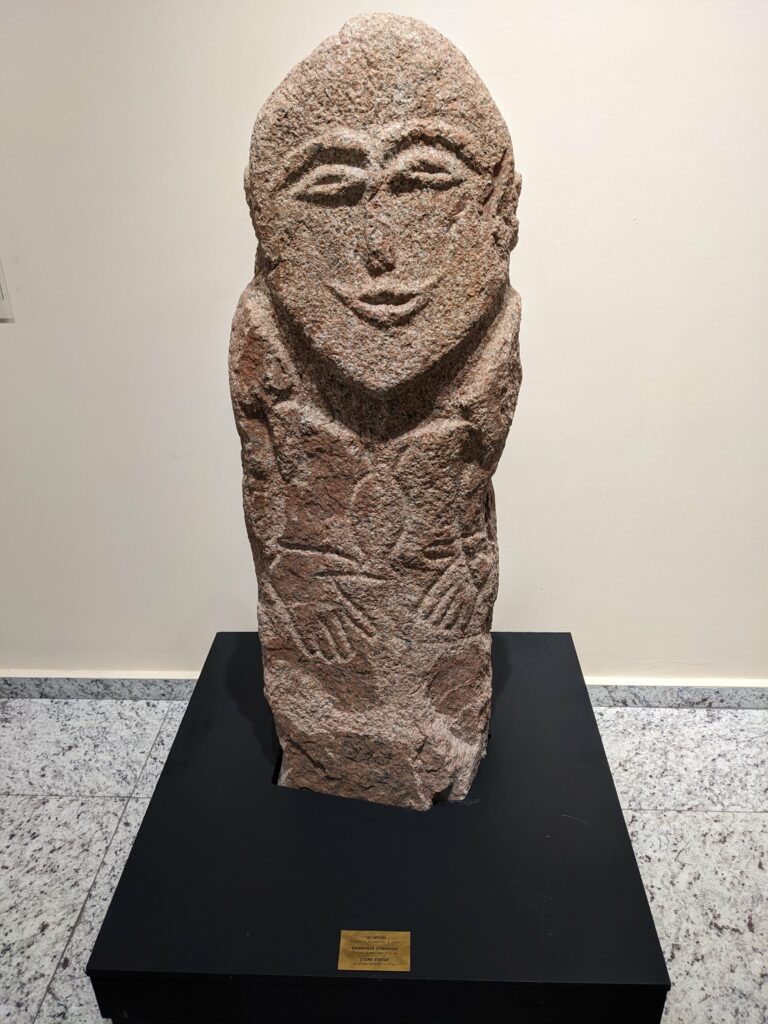

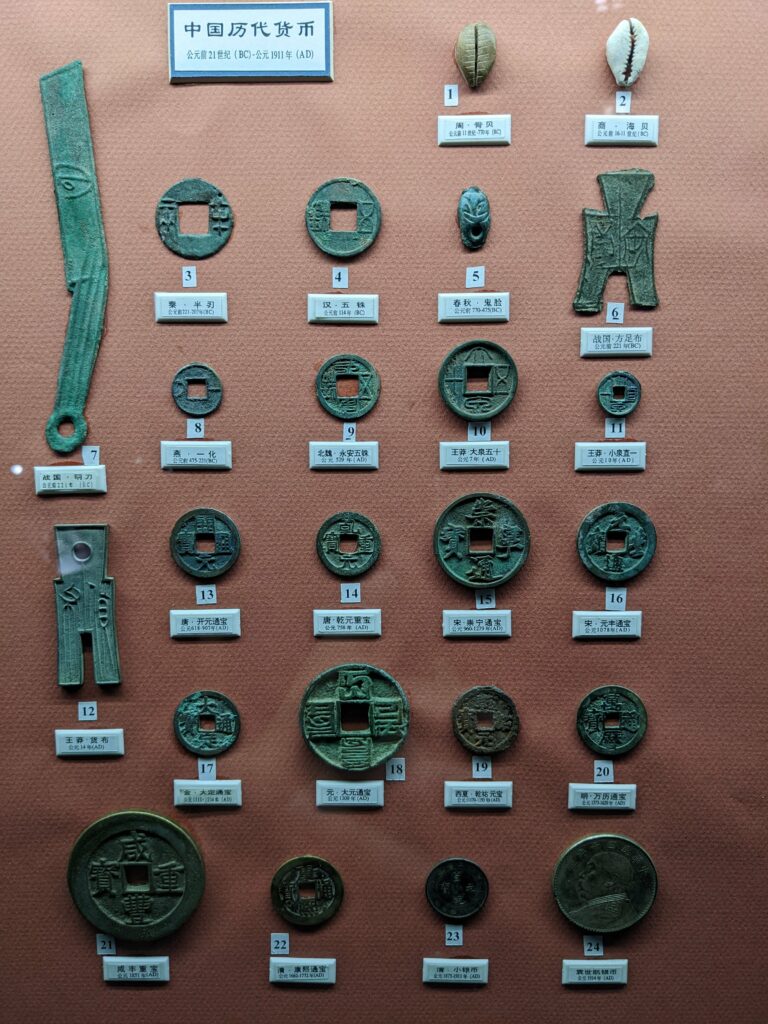

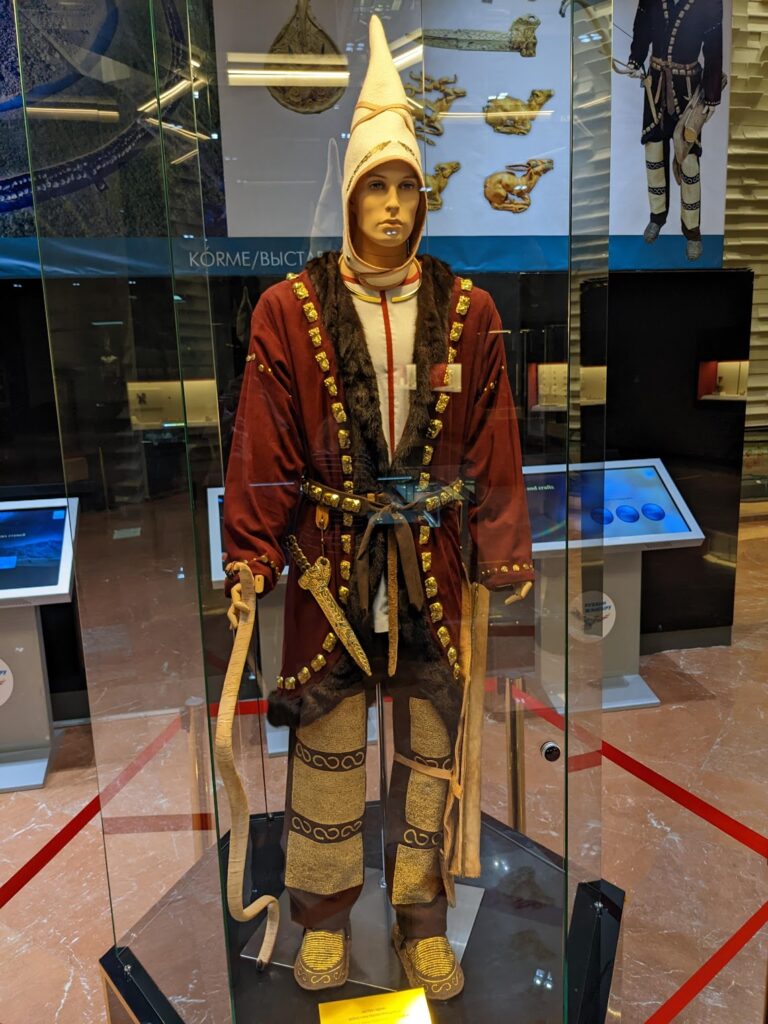

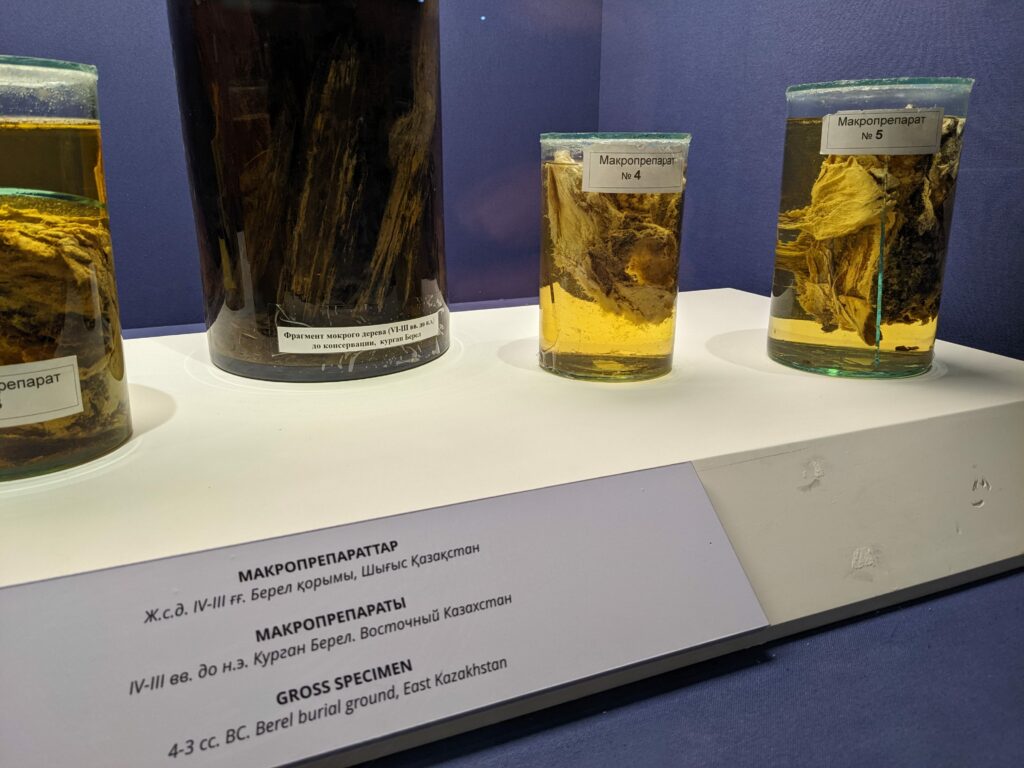

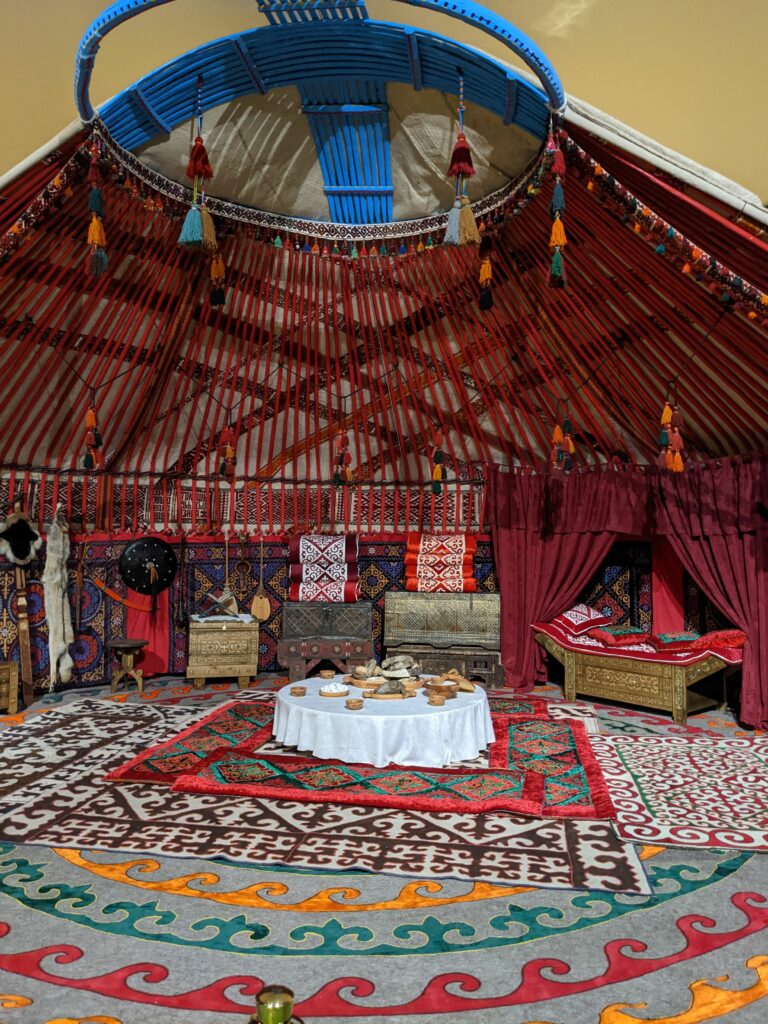

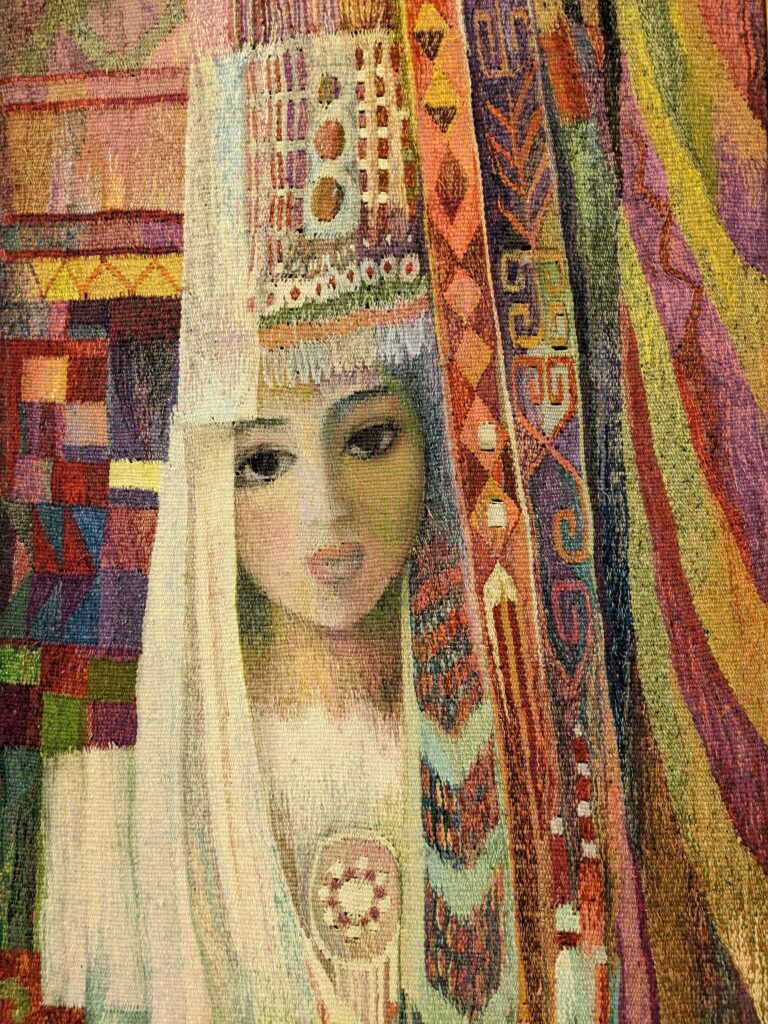

Instead, we spent a few hours exploring the National Museum, and I promise that this wasn’t just because it was lovely and warm. It was one of the most wide-ranging museums I’ve ever visited and I think we only scratched the surface before closing time, but we still saw exhibits on archeology, nomadic life, the Second World War, space travel, fine art, 21st century Kazakhstan, and more.

We even found some information about the three people pictured in the huge murals we’d seen in Aktau in the museum. The portrait on the building closest to the eternal flame in Aktau was Khiuaz Dospanova, the first female officer in the Soviet Air Force, who was named a People’s Hero of Kazakhstan in 2004 for her heroic missions and perseverance after terrible injury.

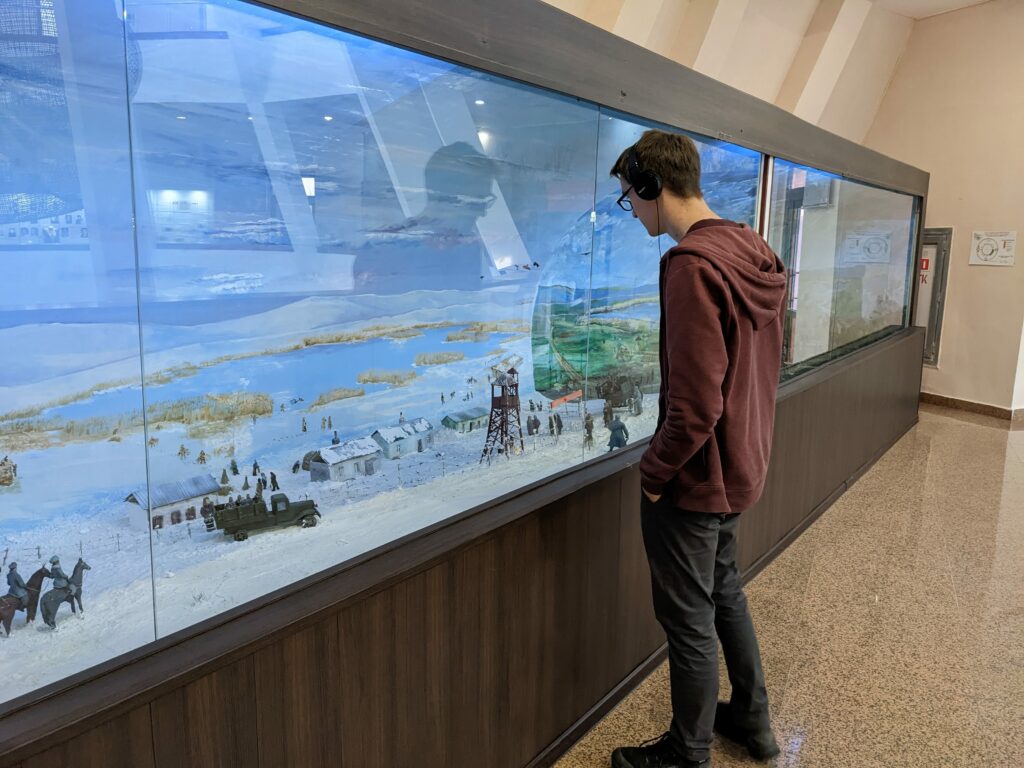

We’d read that a short distance outside of the city was the site of a Gulag (labour camp) for wives of political prisoners during the Stalin years, who were sentenced to 5-8 years for being the “enemy of the people” without any evidence of guilt. We decided to visit the ALZhIR museum and memorial to learn more and pay our respects.

I think it was even more chilling to see the site in the snow, since the conditions at these camps were poor and we read that the women collected reeds from the nearby lake to attempt to insulate their huts. It must have been so cold. Unfortunately, the museum itself was a bit of a disappointment, but it did give us some context about what happened during this period in Kazakhstan, and we read some interesting material about collectivisation on the return bus journey. It was also good to get out of the city and see some everyday life in the town in which the camp had been located.

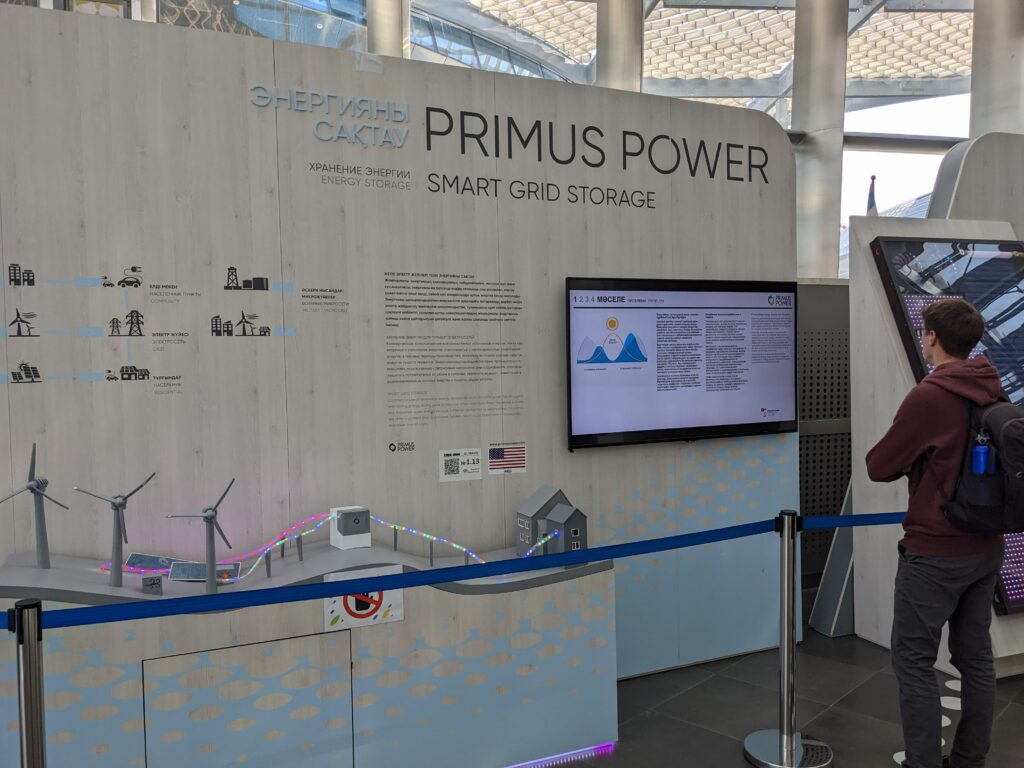

Our final stop before catching our overnight train was the NUR ALEM Future Energy museum. In 2017, the World Expo came to Astana and its theme was Future Energy (somewhat ironically, in a country where renewables comprised only 3% of its electricity generation mix in 2020), and this museum was its legacy. It was housed in one of the buildings from the Expo, an enormous glass sphere that was genuinely impressive and worth a visit for the building alone.

The eight floors, covering future plans for Astana as well as solar, wind, biomass, space, water and kinetic energy, were just the cherry on top. Oli was like a kid in a sweetshop, and described it as “cooler than he could ever have imagined”. Bless him! To be fair, it was a really good museum. I think my favourite thing (which didn’t really relate to energy, but did relate to coffee, one of my great loves) was the exhibit showing the coffee machine that Lavazza have made for astronauts called the ISSpresso – great name! However, the exhibits did leave us wondering why some of the ideas for energy generation weren’t being more widely adopted, if they really were such silver bullets. Oli found a disclaimer on one of the wind power exhibits that answered some of our questions (last slide)…

We loved Astana and were really glad we visited. But from everything we’d read, Astana is the capital of Kazakhstan in name only and Almaty is the real cultural and historical centre. It was there that we were headed next.