Over 19 days, we travelled 2,457 km across the full width of Uzbekistan from the Tájen/Daut-Ata border crossing in the west to the Chernayevka border crossing in the east.

Transport

Between cities, we travelled almost exclusively by train in Uzbekistan, with the exception of the short link between Nukus and Khiva, which we covered by shared taxi. While we’d heard a lot about Uzbekistan’s modern high-speed rail links, we ended up travelling most of the distance by old, slow, Soviet-era sleeper trains due to lack of ticket availability. While they weren’t the fanciest trains we’d ever ridden, they always provided a chance to get to know our fellow travellers, which was mostly a great experience!

Once in town, we largely used buses and marshrutkas to get around. The trickiest part was planning these connections, since little information was available online, and most guides suggested we “ask around”. Given that we don’t speak any local languages, nor do we speak Russian, this was no easy task. Still, we did come across a handful of young adults who were happy to help – sometimes so that they could practice their English but mostly just out of the goodness of their hearts.

In smaller towns, marshrutkas took the form of cute little minibuses. These typically had space for 1 driver, 7 adult passengers, plus luggage and children, although the limit seemed to based on ambition rather than comfort.

Carbon

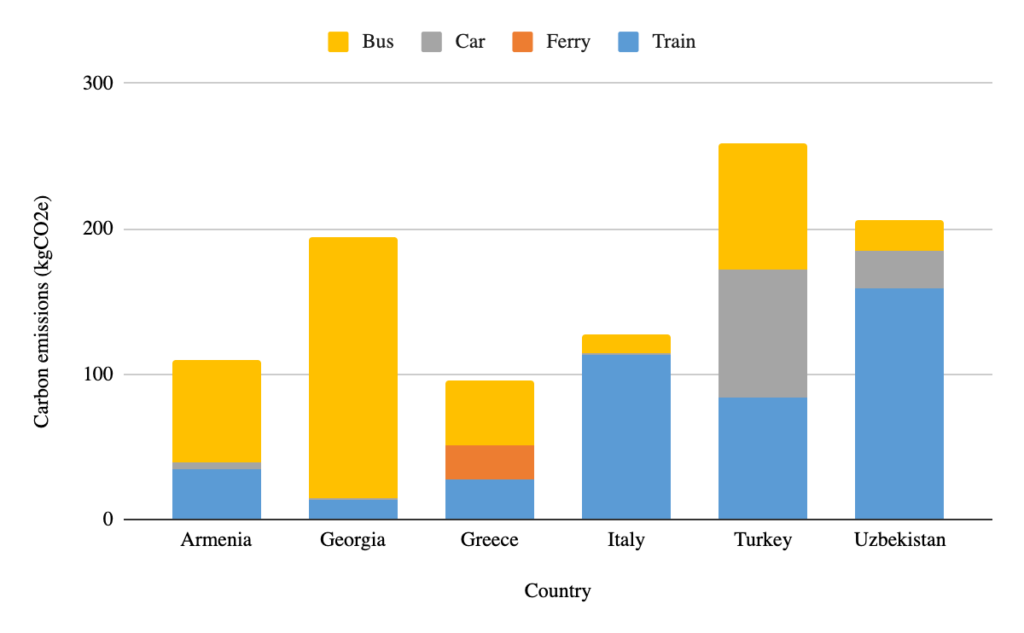

We travelled a long way through Uzbekistan, and because much of this was on less green, low-speed rail, this part of the journey represented our second-highest carbon emissions to date: 206 kgCO2e.

This brings our total emissions to 993 kgCO2e. This was close enough to a tonne of CO2 that we’ve gone ahead and offset this carbon through Gold Standard’s Climate+ Portfolio – our first offset since leaving London! You can find the retired carbon credit in the Gold Standard Impact Registry. This means that as much CO2 has been prevented from entering the atmosphere as was emitted by our modes of transport, and consequently the net carbon emissions are zero. The Climate+ Portfolio achieves this by supporting a variety of emissions reduction projects – from clean cooking solutions and household bio-gas to renewable energy, like wind and solar. While carbon offsetting isn’t as good as avoiding the emissions in the first place, it is a way of taking responsibility for emissions that couldn’t be avoided otherwise.

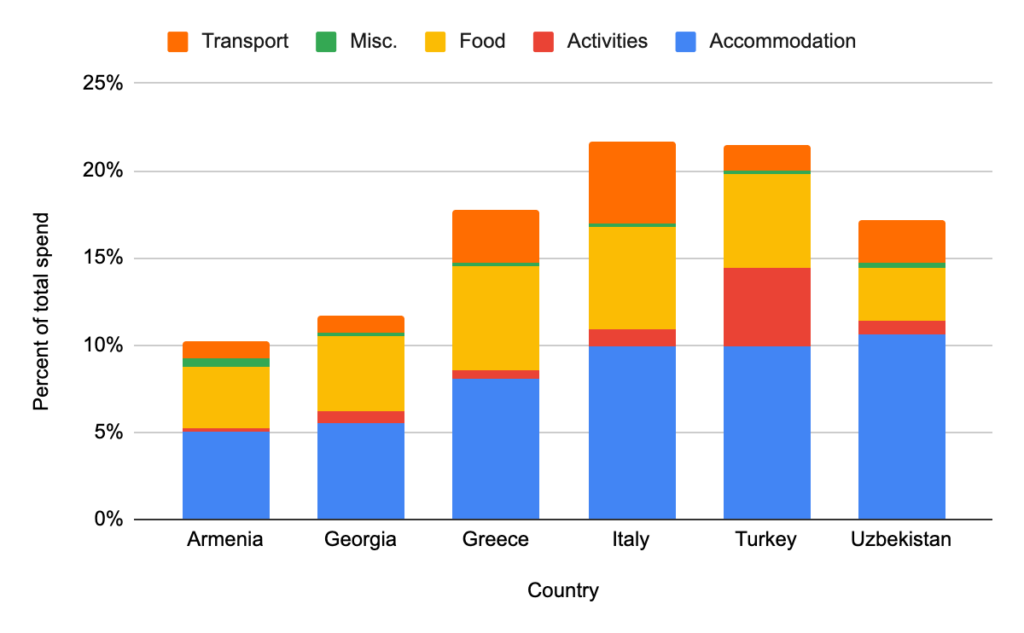

Cost

We spent less money per day in Uzbekistan than in any other country except Georgia, making it pretty good value for money. Accommodation constituted the largest proportion of our spending in Uzbekistan compared to any other country, but this was largely due to a splurge on a fancy hotel in Tashkent (not the Hotel Uzbekistan though!). Conversely, food and drink constituted the smallest proportion of our spending compared to any other country, despite us eating in some high-end restaurants.

Prior to arriving in Uzbekistan, we’d read that many restaurants and hotels required payment in cash, and that working ATMs were few and far between, even in major cities. To prepare for this, we withdrew a fair amount of USD before arriving, which is much easier to change into UZS than withdrawing cash from an ATM. However, electronic payments and ATMs seem to have come a long way in the past few years, and we ended up leaving Uzbekistan with every USD that we carried into the country. Still, better safe than sorry!

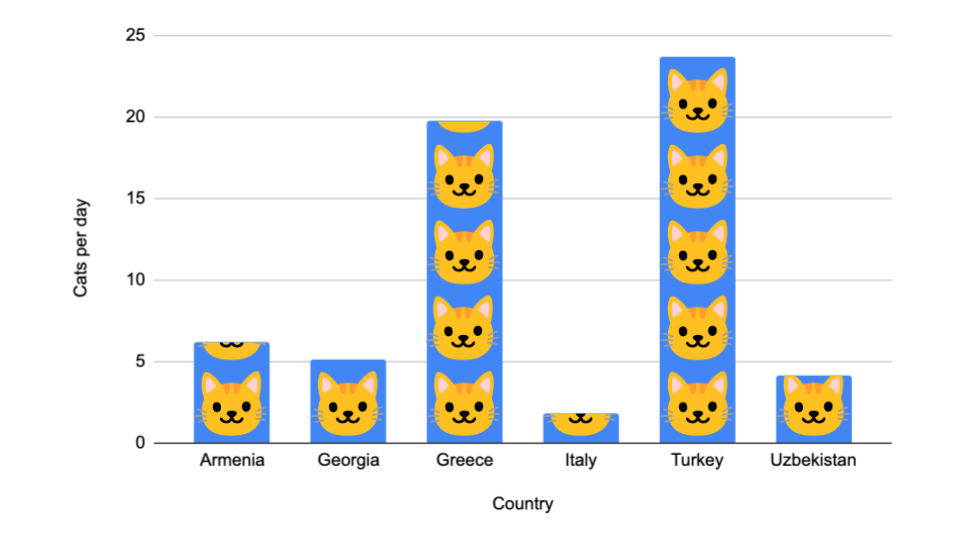

Cats

We saw 79 cats in Uzbekistan, giving it a slightly sad total of 4.16 cats per day, and coming in second-last in the league of countries to date. This feels like a bit of a shame, as Uzbekistan got off to a strong start in Nukus and Khiva, but then fell behind as we moved onto the big cities of Samarkand and Tashkent.

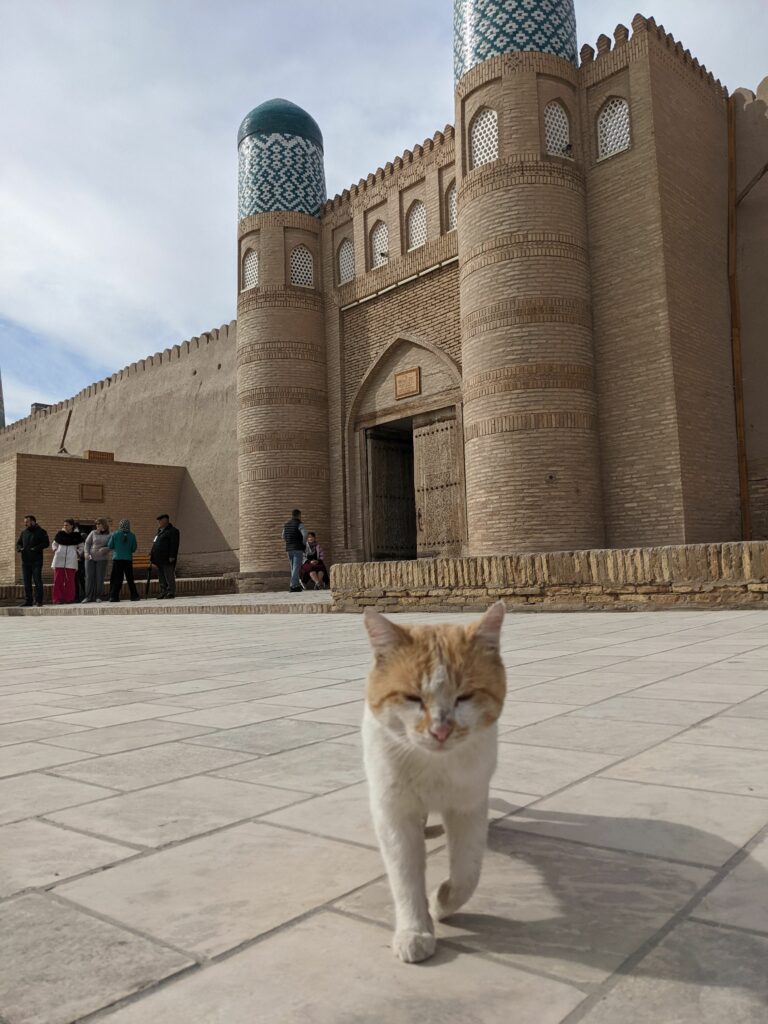

Still, what Uzbekistan lacked in quantity, it made up for in quality…

🏅 Most knowledgeable historian

🏅 most pampered restauranteur

This lovely lady kept sneaking into a restaurant in Tashkent and the staff were frequently escorting her out. At least, we thought they were putting her outside until we realised she was being tucked up in a blanket on a chair in the porch! The staff were taking it in turns to visit and make a fuss of her.

🏅 Sneakiest fare dodger

Despite the language barrier, Baron’s owner fully understood how delighted Sara was to meet him on a bus in Tashkent, and briefly let him out of his carrier to say hello. Apparently he was on his way to the “doctor”. Get well soon, Baron!

🏅 smallest tour guide

🏅 least subtle hide-and-seek participant

Architecture & renovation

Many of Uzbekistan’s historical buildings had been extensively renovated to how they might have looked when they were newly built (or maybe even newer, since we read that traditional building practices aren’t always followed). While this undoubtedly gave the buildings a beautiful and pristine appearance, we found it pretty incongruous to be learning about their long histories while looking at recently (re-)constructed buildings.

In fact, we learned that many of the buildings had been renovated (and even extended) many times over the years, following various sackings or natural disasters. This made us realise that there’s no right or wrong way to maintain such buildings (cathedrals in the UK have surely had many a new roof, for instance), but the level of polish we experienced in Uzbekistan was well beyond what we’d seen elsewhere.

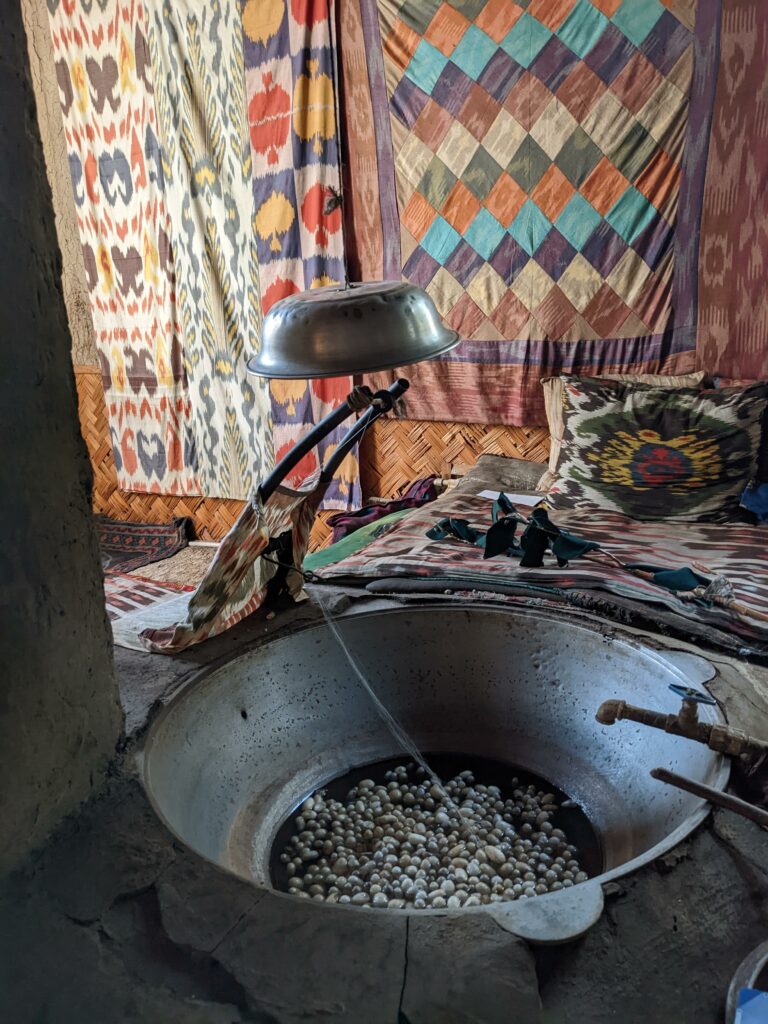

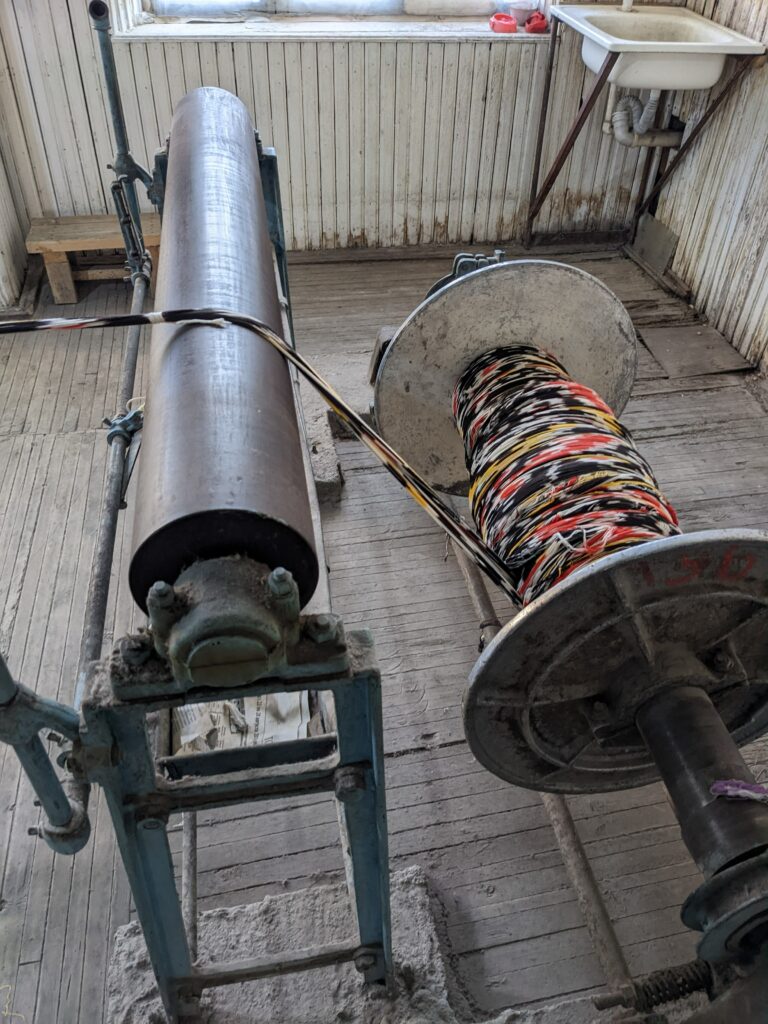

We felt lucky to have seen as much local life as we did, since we read that traditional markets were next on the government’s hit list because of a perception that visitors would find them unsanitary. Indeed, we spent quite a while in Khiva searching for a local bazaar that we’d read about, before we eventually realised that perhaps it had been razed in favour of the huge, sterile plaza which extended all the way to the train station.

To get to Uzbekistan, we took a short flight across the Caspian Sea and two trains across western Kazakhstan. Following our stay in Uzbekistan, our journey circles back into Kazakhstan, to visit the cities of Shymkent, Astana and Almaty. We’ll round up both visits to Kazakhstan in a single post once we leave Kazakhstan for the second time.